Richard Hine and Susan Treeby

Richard Hine and Susan Treeby

Acknowledgement

This page was written and researched by Richard Knott. It is from his website 64 Regency Ancestors. It is an excellent history, and it is reproduced here with his kind permission. Please also bear in mind that the notes at the bottom of this article are his notes not mine.

Richard Hine (1804-1847) & Susan Treeby (1808-1870)

Family tradition has it, (Note 1) that Richard and Susan eloped to London, Susan’s only possession being a silver spoon that she took as a memory of her family. When her father found out about the elopement, he sent one of his sons after them with £100 and instructions to bring them back to Devon. Susan was found by her brother and a good time was had by everyone on the £100. All was not forgiven.

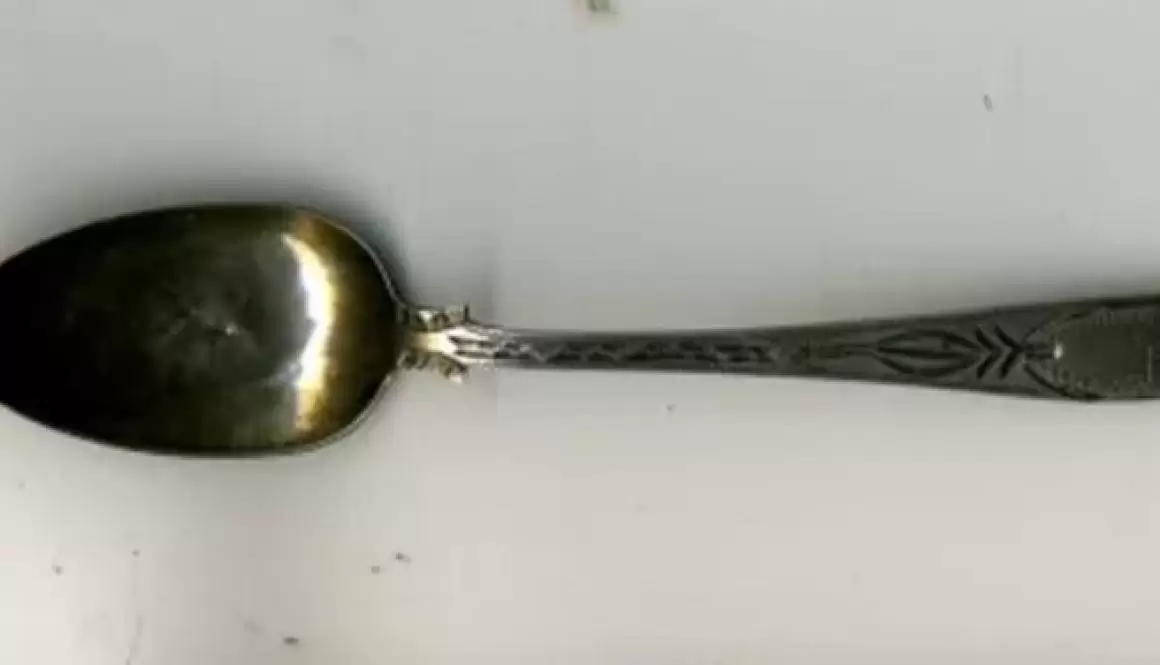

The Silver Spoon

The spoon still exists, inscribed with an ‘M’ above a ‘WT’, and dated to the end of the 18th century. Susan’s parents were Mary and William Treeby but, by itself, it offered no support for the story. Susan and Richard actually married in Ugborough, Devon, rather than London, after banns had been read; but it was his home village rather than hers and, significantly perhaps, it was only a few weeks after her father had died. Had William not approved of the match? Rather than elope, maybe that had simply waited until he was not there to object. But even this version looks less likely when William’s will is examined. He and Mary had nine surviving children and all of them are mentioned. Six receive five pounds each, but three were give a bed each and a third of everything else: one of his sons and both his unmarried daughters, including Susan. It was written shortly before he died and might be expected to mention Susan’s possible marriage if it was an issue.

One thing is certain: Susan’s family was better off than Richard’s and her father’s disapproval would have been understandable. Richard himself was a limeburner. Lime was needed for farmers, builders for mortar, and tanners to remove the hair from hides, but the job of burning the limestone in kilns was unpleasant and dangerous. The men would lay kindling on a grill at the bottom of the kiln, and then build alternate layers of fuel and stone. Controlling the fire would allow the middle section to burn while the top part would be heated by the smoke and the lower part could start to cool; removing the lower layer and topping up the kiln would allow it to run continuously, although not every kiln operated this way. Apart from the physical exhaustion caused by moving the rock and fuel to and from the kiln, the fumes could cause lung disease and the lime dust mixed with sweat to cause chemical burning on the limeburners’ skin. The kilns provided continuous heat, so they were places that tramps sought out at night, but often they would be found dead in the morning, killed by the fumes. In Devon most of the lime was used to treat the soil and kilns were spread across the county, mostly close to quarries so that the transport costs would be reduced and there was somewhere to tip the waste products after the lime had been removed. The remains of one are still visible next to a disused quarry opposite Ennaton farmhouse just East of Ugborough, which may have been where Richard worked, although a number of limeburner’s cottages were located immediately next to the quarry itself.

Plymouth

Richard, named for his grandfather, had been born in Ugborough where his family had laboured on the land and in the quarries for generations. (Note 2) He was the eldest son of John and Ann who lived at the Northern end of the parish in a hamlet called Bittaford looking out across South Dartmoor. His nine siblings were born over a period of over thirty years, so Richard would have been an adult when the youngest, George, was born, but an apparent lack of ambition or opportunity for those in the family meant that George, too, worked at the quarry, and all their sisters who married chose labourers as their husband (Note 3). That said, another brother became a postal messenger and John, the brother closest to Richard in age, was farming 100 acres before he was thirty, and later bought the 50 acre Hill View Farm in Ugborough, which continues as a farm to this day.

It clearly was possible to leave behind the poverty of the quarry for some.

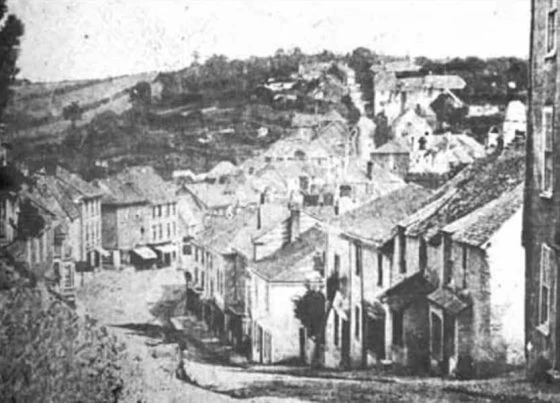

Swanbridge Mill, Modbury

Richard married Susan Treeby in 1834. She had been born in Modbury, four miles South of Ugborough, and was the youngest child of one of the town’s millers, William. Modbury was a large village but the surrounding hills made it virtually invisible as the village was approached from the road. Its three streets, each with their own shops, ran steeply through the village, and at the centre sat Swanbridge Mill. (Note 4) The mill was the most central of Modbury’s seven mills, and the first of four on Aylestone Brook, a small waterway that struggled to provide enough power for all the mills. Unusually, it was also fed by Tuckers Brook, yet still needed a large pond to power the mill when the streams were not full. A fourteen foot wheel drove two sets of mill stones, its large width compensating for a fairly small drop in the water, and had probably been installed in 1827 when William had enlarged and modernised the mill. It was the oldest mill in the town, mentioned in the 13th century, and was to earn a living for at least three generations of the Treeby family. As the youngest of at least eleven children, Susan would have had a very different childhood to Richard. The lack of a good supply of water in Modbury would have caused problems for all the millers in the town, but she was likely to have had a comfortable childhood, while her parents ran the mill and her brothers prepared to take over eventually (or become involved in related occupations, such as being a maltster).

As suggested earlier, it may be that Richard and Susan had waited to marry until William had died; it may be that the money inherited from her father had allowed Susan to feel confident that there was some financial security if she married; or their marriage and William’s death may be unrelated. Whatever the reason, his dying meant that the couple probably spent their wedding night on William’s own bed that he had left Susan in his will, and they had in the knowledge that they also had a significant amount of money to help as they started their life together (Note 5). At almost thirty years old, Richard may already have been suffering from the effects of his work, but in 1841 he was living in Ugborough, close to his parents, with four young children to support. The family suffered a tragedy the following year when Thirza, one of Richard’s sisters, fell into a fire and was burned to death, so his last few years were not happy. In the end, it was not his job that killed him, but typhoid, a killer for large numbers of poor people whose lack of proper sanitation inevitably led to problems. The hot summer of 1846 meant that various diseases were rife across the country and, after four weeks of suffering, Richard was one of the 30,000 who died in the typhoid epidemic of 1847. A fifth child was barely two, and the eldest was yet to become a teenager, so Susan faced difficulties. Many in her position remarried, but she worked as a labourer to bring in some money, but moved next door to John Hine, her father-in-law, in Bittaford so that he and Ann could help with the children.

As soon as he could Richard, the eldest child, moved away from home to live with relations who owned a farm, and not long afterwards he moved further away to become apprenticed to a shipwright and a secure future. At the same time both John and Ann Hine died, so Susan was left alone; but, by now, Mary Jane, the youngest, was approaching ten and was soon to move away herself to be a house servant. John, the youngest son was soon to move to Dunster in Somerset where, as a mason, he worked on the castle. It was William, the second child, who remained at home, doing manual work, but with the excitement of the railways as an employer rather than the local quarry. He married but remained in the hamlet and, when Susan died in 1870, was still there in the village where his family had been for generations. Susan was in her sixties, but had probably not had the life she (or her father) had dreamed about. It seems that she married for love, but her husband had died nearly fifteen years earlier, and her whole adult life had been a struggle financially. Her legacy is a silver spoon and a romantic story that probably has little basis in truth.

Notes

1. I have a letter written in 1971 by my grandmother, the great-granddaughter of Richard and Susan. Later she claimed that she had meta Treeby descendant at a YWCA conference who knew the same story. There is no other evidence beyond this oral tradition

2. Although Richard’s father, John, was a labourer, John’s father and grandfather (both called Richard) may not have been. The Sherborne Mercury in 1775 refers in a sale to a Richard Hine, tenant of Bitteaford Bridge; and a Richard Hine swore an oath of allegiance in 1723 when very few of those doing so – less than 1% – were labourers

3. The eldest child, Mary, was called an ‘annuitant’ when she was living with her brother, John, in 1871, suggesting she inherited some money; and yet her husband had been a gardener

4. The description and photograph of the mill, together with the early photograph of Modbury, come from the following site: Modbury Heritage.

5. William’s estate was worth about £300. Susan inherited one third after the other bequests so she might have received about £50 – about £1500 in today’s prices