Alexander Thomson and Christina MacInnes

Alexander Thomson

Alexander Thomson was born in the village of Coll on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland in 1813. His parents were James Thomson and Mary MacAuley.

Christina MacInnes

Christina MacInnes, also known as Chirsty, was born in the village of Parks, Lochs on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland in 1812. She lived to the age of 101 and died in Tong.

Back and Coll

The photograph opposite shows an aerial view of the villages of Back and Coll.

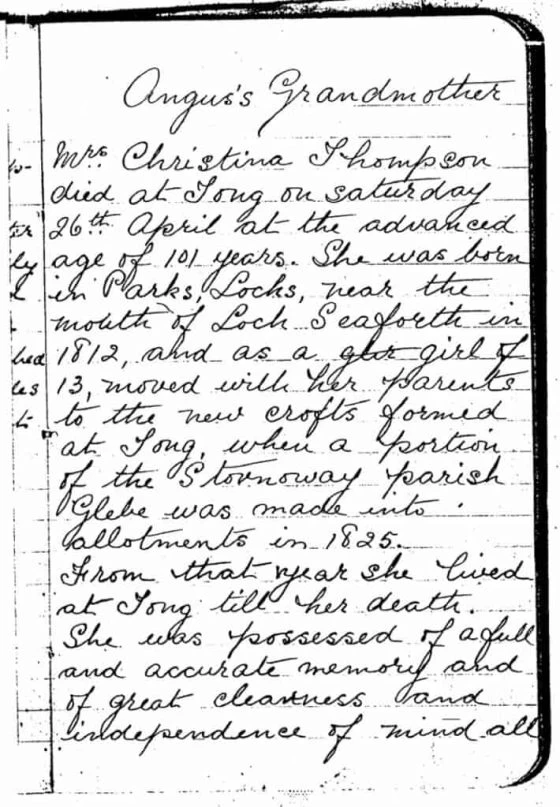

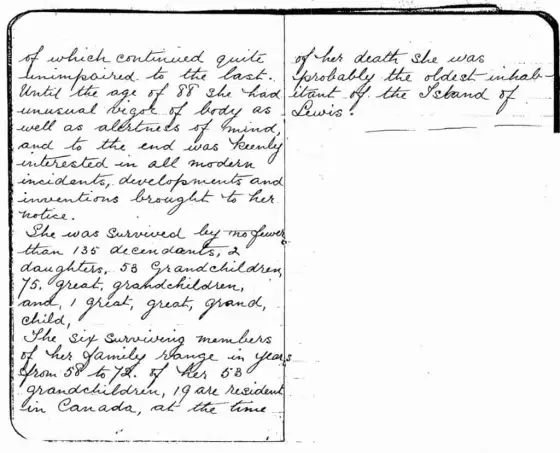

Angus’ Grandmother

“Mrs Christina Thomson died at Tong on Saturday 26 April at the advanced age of 101 years. She was born in Parks, Lochs, near the mouth of Loch Seaforth in 1812, and as a girl of 13 moved with her parents to the new crofts formed at Tong, when a portion of the Stornoway Parish Glebe was made into allotments in 1825.

From that year she lived at Tong till her death.

She was possessed of a full and accurate memory and of great clearness and independence of mind, all of which continued quite unimpaired to the last. Until the age of 88 she had unusual vigor of body as well as alertness of mind, and to the end was keenly interested in all modern incidents and inventions brought to her notice.

She was survived by no fewer than 135 descendants, 2 daughters, 58 grandchildren, 75 great grandchildren and 1 great, great, grand child.

The six surviving members of her family range in years from 58 to 72. Of her 58 grandchildren, 19 are resident in Canada. At the time of her death she was probably the oldest inhabitant of the Island of Lewis.”

The Thomsons of Tong

My father spent his retirement visiting the Record Office in Edinburgh. He meticulously traced the history of his “Thomson” ancestors. I never thought anything of this at the time, but I now realise that he really only ever researched the history of the Thomsons. A bit like he was only interested in following the Y Chromosome.

My objective is the opposite. I want to trace ALL the ancestors of my children and to try to tell the human stories behind them where I can. Sufficient facts and figures to create the context, but the emphasis to lie on stories and anecdotes.

When my father could go back no further than James Thomson. he had a change of plan and decided to fill in by tracing the descendants of James Thomson. This was a massive task, but we shared the idea of creating human interest stories. He traced many Thomsons, who had emigrated to all parts of the globe and wrote to them, inviting them to write to him and tell him about their recollections of emigration; and write to him they did. He was soon creating a collection of anecdotes, first hand accounts of leaving Lewis.

Crofting

Outside the town of Stornoway life in the rural areas was dependent on the crofting system. Each croft was an area of land approximately 6-7 acres or 2.5 hectares,. The crofts were close together in village communities. Although the crofter did not own the land he had absolute security of tenure following the Crofters Act of 1885. He could sell the croft or will it to whomsoever he wished. But in selling the croft he could only charge the value of improvements effected during his tenure. He was usually succeeded by a member of his family.

The croft could support only one family. As a family grew to adulthood all but one had to find a livelihood elsewhere. This drove many men and women to emigrate to distant lands such as the US, Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and to some European, countries. Between 1922 and 1929 three ocean liners left Stornoway with many emigrants to the US and Canada. The last ship which left in 1929 discharged its human cargo in the US and Canada as the great financial crash of 1929 took place.

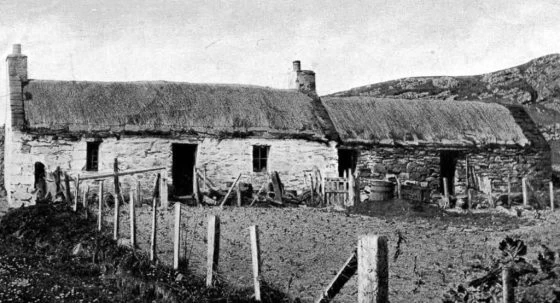

Gathering Peat for Fuel

Each crofter had the right to graze two cows on the common grazing land round the village and to have a flock of sheep on the moorland some miles away. In the summer the common grazing was closed for six weeks in June and July. During these six weeks the cows had to be grazed on the croft or taken to the moor some distance away. On the moor each family had a very small bothie or shieling usually beside a quiet, secluded loch. These shielings were often in village groups. Each shieling was made of stone and earth roofed over by a large tarpaulin. As life was largely in the open air the shieling was just big enough to hold a bed, two chairs and a fireplace.

Fortunately in June and July the weather was always friendly. The shieling was usually occupied by grandmother and one or two grandchildren to act as cowherds. The cows were allowed to roam during the day and had, therefore, to be kept under observation. Life in the open air in June and July was warm and idyllic. It is not surprising that the shieling appears frequently in Gaelic song and poetry.