James Thomson and his Native Family

Important Notice

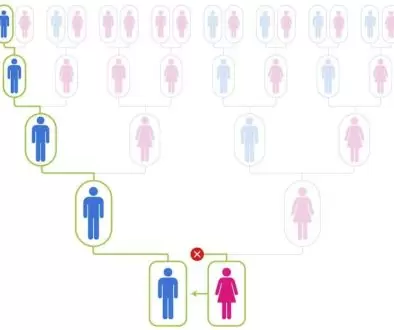

Since this article was first published I have made contact with the family of Caroline Thompson and as a result of DNA testing it now appears that James Thomson was not the father of Caroline Thompson. Work is ongoing to clarify and confirm the situation, but the family of Caroline Thompson have suggested that this article should remain online until tests are complete and a formal correction can be made.

James Thomson and his Native Family

This article is the second part of the story of James Thomson and Isabella MacIver. The first part of the story is told in The First Lewis Woman in Athabasca. It is a good idea to read the first part of the story before reading this article.

The illustration opposite has been reproduced with the kind permission of the Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre. With it’s depiction of the wildlife of Northern Canada, it evokes, to me (a European), the spirit of North Athabasca, where the story that follows is set.

It is also a beautiful piece of artwork, in it’s own right. I am not familiar with the wildlife of the area, but I believe I can see eagle, fox maybe wolf, buffalo and beaver. Perhaps a muskrat top right, the others I can’t identify, but I still love the picture.

I must first acknowledge and thank Patricia McCormack, Professor Emerita from the Faculty of Native Studies, University of Alberta, who unearthed the story about James Thomson and his native wife. She delivered a paper to Ethnohistory, 30 Sep – 4 Oct 2009 at New Orleans, Louisiana. Her paper was entitled “James Thomson and his fur trade wives: Fur trade reality or the soap opera of Fort Chipewyan?”

She has kindly given me permission to use material from her article on this web page.

Hudson’s Bay Company

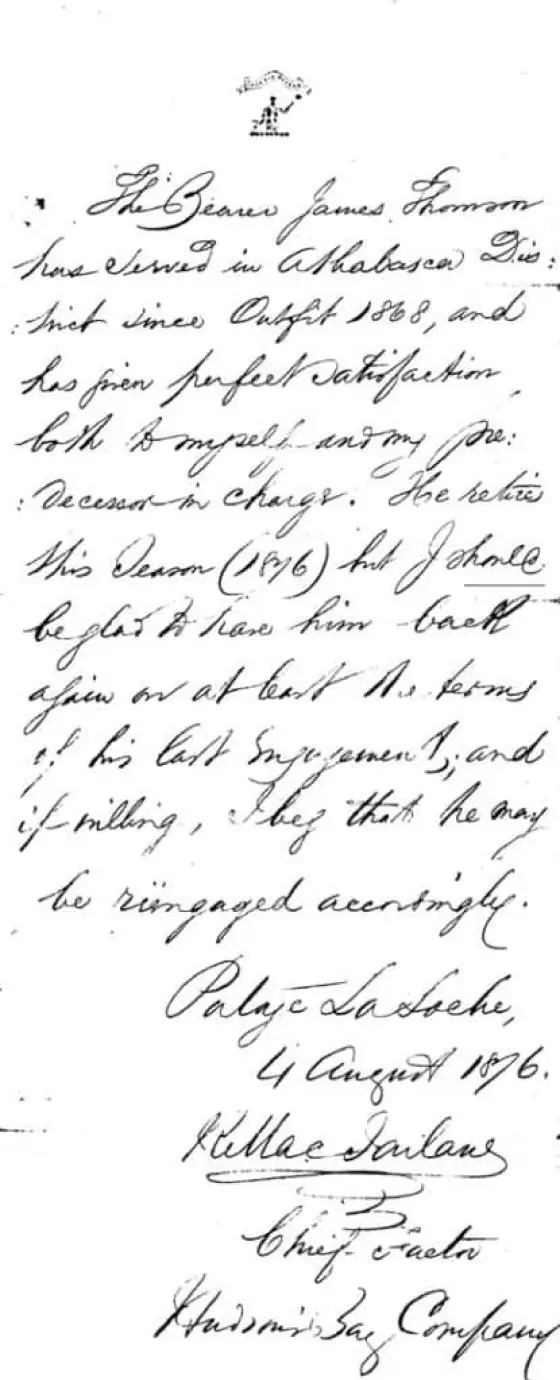

James Thomson, who was originally from the Isle of Lewis, Scotland had been employed as a labourer by the Hudson’s Bay Company since 1868. By 1876 his contract was coming to an end and the letter opposite is a testimonial given to him by his employer, but also a letter to his superiors requesting his re-engagement for a further term. The letter transcribes as follows:

The Bearer James Thomson has served in Athabasca District since [Outfit?] 1868 and has given perfect satisfaction, both to myself and my predecessor in charge. He retires this season (1876) but I should be glad to have him back again on at least the terms of his last engagement, and if willing I beg that he may be re-engaged accordingly.

Portage La Loche, 4 August 1876

Hudson’s Bay Company

James Thomson continued to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company until 1885, so presumably he was awarded a contract renewal.

Hudson’s Bay Company

I like this coat of arms for the same reason that I like the illustration in the first paragraph.

The coat of arms has a number of components which have remained remarkably consistent over time. It is composed of a silver shield with a red cross (the cross of St. George) with four brown beavers, one in each quarter. Above the shield is the crest, which depicts a fox sitting on a red cap, the Cap of Maintenance, which is trimmed with ermine.

The shield and crest are supported by two elk. The earliest representations show animals whose antlers are more like caribou than what would be recognized as elk, but since no Europeans, or at least none at the College of Arms in England, had seen an elk, the animals on the original coat of arms were in fact quite bizarre looking.

According to E E Rich, professor of Canadian fur trade history and editor of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society from 1937 to 1959, the animals were supposed to be moose. A revised version of the coat of arms issued on Canadian share certificates in 1961 transformed the ambiguous “elk” into unmistakable moose.

James Thomson

The previous post told the story of Isabella MacIver and her journey from the Isle of Lewis in Scotland to Fort Chipewyan in Northern Alberta, Canada in 1881.

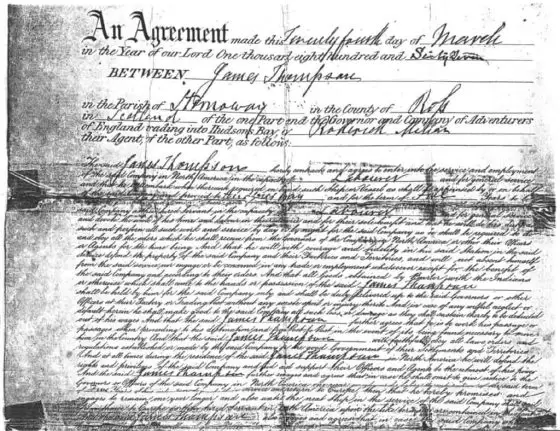

James Thomson was born about 1844 in the crofting village of Tong, on the Isle of Lewis, Scotland. James joined the Hudson’s Bay Company labour force in 1868 and sailed to York Factory. He was posted to Fort Chipewyan, where he advanced from “labourer” and “middleman” to “fisherman”.

In 1876 he returned home to Lewis at the age of 32, and the following spring on 27 April 1877 he married Isabella Maciver, also from Tong and about 13 years his junior. She would have been a young girl, only 11, when he left for Canada. She was grown up and of marriageable age when he returned. James was probably a good catch, because his years with the Hudson’s Bay Company had given him a bank account. Perhaps he seemed dashing and exotic as well, back from the fur trade, undoubtedly with tales to tell. In 1878 he returned to Fort Chipewyan, and it is probably safe to assume that he expected Isabella, like other Lewis women, to remain at home in Lewis.

It seems that James Thomson may have had a liaison with a native Chipewyan woman called Louise Encore, by whom he is alleged to have had a child Caroline, who took the surname Thomson, to reflect what she believed to be her parentage, allthough she spelt her surname Thompson. It is not clear whether this was a casual liaison or possibly a marriage à la façon du pays, which I understand to mean an arrangement according to the customs of the local Chipewyan population.

I took an ancestral DNA test last year and I note that I have genetic DNA matches from several people in the Edmonton area, who also have native American ethnicity in their DNA. The percentage DNA match indicates a distant cousin, but as the common ancestor between myself and any descendants of Louise Encore would have been my great great grandfather, who was also James Thomson’s father, it is perhaps not surprising.

Making Dry Fish

Isabella MacIver, when she arrived in Fort Chipewyan, would have lived the life of a typical labourer’s wife. Her earlier life on Lewis would have accustomed her to hard work.

Two weeks after their arrival at Fort Chipewyan, James was sent to establish a fishery on Lake Mamawi. He took with him one assistant and two women, presumably their wives. The women’s job was “to make dry fish”.

Isabella would have been well accustomed to filleting herring on the quayside in Stornoway, but she would have had to learn the art of making dry fish. In Europe, we talk about dried fish, but that should not be confused with the traditional Chipewyan dish, which is always known as “dry fish”.

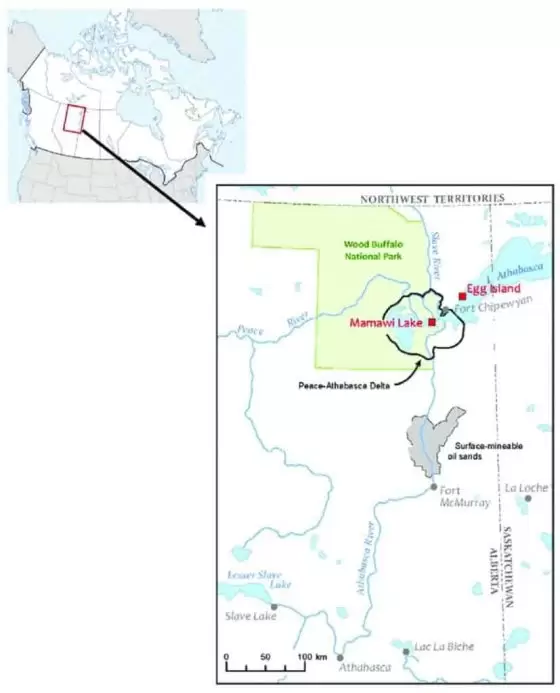

Lake Mamawi

They were at the Lake Mamawi fishery until the middle of October, perhaps a second honeymoon for them. At the end of October, James was sent out to Goose Island to work at the major fall fishery, where several men and their families were stationed. Isabella undoubtedly began to learn a little Cree, English, French, and possibly even Chipewyan at this time.

The fishermen remained at Goose Island until the day before Christmas. The post journal noted that all the Protestant labourers dined at Wylie’s; that would have included James and his wife. Although Isabella would have worked with her husband, she may also have been treated as something special by the other Scotsmen, thanks to her Lewis origin, and afforded special favours not necessarily granted to other women.

They had three children in Fort Chipewyan born one year after another, Marion on 28 February 1882, James Alexander 12 March 1883, and Catherine in May 1884. Isabella would have been assisted by a competent local midwife. The children were all baptized at St. Paul’s Anglican Church by Reverend Reeve. The family lived at Fort Chipewyan until 1885, when they returned to Lewis.

Return to Lewis

Back in Lewis, James became a merchant and trader, and Isabella worked in the shop, producing butter, cheese, and jam to sell. Later James purchased a fishing boat and hired a crew. He had been working his mother’s croft in Tong (no. 15), and he acquired the croft in his own name in 1902. Five years later, he bought a second croft in Tong (no. 17). They had ten children, most of whom survived. They celebrated their Golden Wedding anniversary in 1927. James died in 1929 at age 85, and Isabella in 1949 at age 93.

Caroline Thompson/Thomson

Patrica McCormack was reading the 1899 Half-breed scrip applications from Fort Chipewyan and found an application by one Caroline Thompson. She was born, she said, on the 15th of December, 1880 at Fort Chipewyan. Her mother was a Chipewyan Indian (noted as a “Pure Indian woman”) named Louise Encore. Caroline named James Thomson as her father but added a sad note to the application:

“I am an illegitimate child. My father was James Thompson a Scotchman who is now in Scotland. He never recognized me as his child and has never supported me. As a matter of fact he has repudiated me as being his child.”

Louise Encore

It was only by luck and chance that Professor McCormack had earlier discovered the story of the Thomson family and was able to think about the implications of this new information. Assuming that Louise Encore carried her pregnancy for a full nine months, she would have become pregnant about the middle of March, 1880. That meant that James Thomson was involved in a sexual relationship with Louise, but probably not marriage à la façon du pays, for some period during the winter of 1879-1880, at the same time that his wife Isabella was making her own plans to travel from Lewis to York Factory on Hudson’s Bay.

Caroline Thompson’s Birth

But if James Thomson went out to Red River on the first boats of the season, in late May or early June, it is possible that he would not have known when he left that Louise was pregnant, and in any event he may have told her that he was not returning to Fort Chipewyan, now that his Lewis wife was arriving. Perhaps he thought that the Company would station him elsewhere.

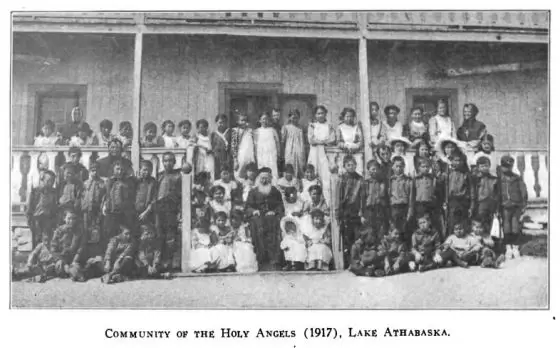

Community of the Holy Angels

Louise Encore delivered her baby daughter in the middle of December at Fort Chipewyan. She and baby Caroline left for Fond du Lac, a post for Chipewyans located at the other end of Lake Athabasca, possibly in the spring of 1881 when it was warm enough to travel or, more likely, when the lake opened in June. She may have had family there, or they may have been encouraged to leave by the Company factor.

Macfarlane or one of the other men, who knew that Thomson was returning with his Scottish wife, probably before James and Isabella arrived in August. Maybe both factors were at work. Louise and Caroline lived at Fond du Lac in 1881 and 1882. But then Louise died (when Caroline was “about one year old” – from scrip application), and Caroline was sent to live at the Holy Angels convent in Fort Chipewyan, where she was raised by the Sisters of Charity, more commonly known as the Grey Nuns.

Although James and Isabella were kept busy out of town at the fisheries for most of the fall following their arrival, we can engage in another point of reasonable speculation: the women of Fort Chipewyan would have made sure that Isabella knew about the Chipewyan woman and her daughter by James. One can imagine the scenes that must have followed between Isabella and James, the accusations and tears from Isabella, and the denials by James. That was almost certainly why James formally repudiated his illegitimate daughter, although we do not know the form it took. Yet Isabella and James were stuck with each other at Fort Chipewyan; they would have found it difficult to divorce. They obviously found a way to move on, to preserve their marriage, and the possibility of James having fathered this daughter became a secret that was not part of the family’s oral tradition.

Childhood in the Convent

Caroline Thomson was a child in the convent while her two half-sisters and one half-brother were born. Perhaps she was told about them; she may even have met them; but at such a young age it would not have meant much to her. She was five years old when her father left Fort Chipewyan to return to Lewis. Nevertheless, she persisted with his surname, which meant that she believed what she had been told about her parentage and that James had “repudiated” her as a daughter.

It seemed that Caroline chose not to self-identify as a Chipewyan woman, perhaps because she had been raised in the convent. Had she been raised by a Chipewyan family after her mother died, her life and identity would have been different.

She grew up a Roman Catholic, literate in the French language of the Sisters, with a Scottish father (or believing that she did). The scrip application indicated that it had been “read over and explained in the French language,” and she signed her name “Caroline Thompson.”

Caroline lived in the convent until July 1897, when she left to work as a servant for long-time employee Pierre Mercredi. She was then nearly 17 years old. Pierre Mercredi had gone to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1879 and must have known her father well, both from living in Fort Chipewyan and from working for the same company for six years. I like to think that Pierre believed that James had not done right by his daughter.

Giving her a job and thereby providing for her was the right thing to do. While girls raised in the convent often married when they left, Caroline was described as “Crippled (Lame)” in the 1901 Census, which would have made it more difficult for her to find a husband. In April 1898, she went to work for trader Colin Fraser, also as a servant. Servants were not common at Fort Chipewyan, but both women and men occasionally worked for well-to-do traders.

A female servant at Fort Chipewyan would have done domestic labour in the household, housekeeping, cooking, sewing, and childcare, something for which Caroline had been well trained by the Grey Nuns. Because Caroline had learned to read and write, and probably to do arithmetic, one wonders if Fraser might have found other uses for her in his business.

Scrip Application

She was still working for Colin Fraser when she applied for scrip. It is intriguing that she applied for land scrip, not cash scrip. The Half-breed scrip process in Canada was intended both to settle the Aboriginal claims of mixed-ancestry people who did not enter into treaty and to provide them with land to be used for farming. But land scrip was mostly worthless to northern people, because it was not possible to turn such scrip into land ownership in the north at that time. Land had to be taken in southern areas that had been surveyed and opened to homesteading. One wonders if Colin Fraser, who had good contacts in Edmonton, advised her to make such an application, thinking that he would help her get the land and then profit from its sale. She applied for scrip on 7 August 1899. Around the same time, she became pregnant, and her baby, Rosa Alberta Thompson, was baptized at the Holy Angels Mission on 20 May 1900 as the “illegitimate daughter of Caroline Thompson.” She was James Thomson’s granddaughter, though it was unlikely he ever knew about her.

Colin Fraser’s Household

Caroline Thompson, applied for land scrip. She identified herself as a “servant,” having worked for both Pierre Mercredi and Colin Fraser after she left the Holy Angels Convent in 1897 at the age of seventeen. She made her application in French, which she would have learned in the convent (LAC, RG 15, v. 1369).

This photograph shows the household of Colin Fraser. Caroline Thompson, who worked as a servant for Colin Fraser may well appear in this photograph, although we can’t be sure which one she is.

Colin Fraser, Fur Trader

Colin Fraser did not arrive in Fort Chipewyan until 1887, so he would not have known James Thomson, though he undoubtedly heard about him as he became part of the local community.

John Arnott

Because Rosa Alberta was described as illegitimate, it suggests that Caroline married after the birth to John Arnott, a 47 year-old Englishman who was a returned Klondiker. In the 1901 Census of Canada, she was listed as John’s “Scotch breed” wife, and their daughter Alberta was one year old.

Caroline still had her land scrip, which was later listed in her married name, Caroline Arnott. John Arnott, who was working as a fisherman for an independent trader (Charles Smith), froze to death in a wicked snow storm in March, 1902. He was buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery on the shore of Lake Athabasca.

Postscript

An earlier version of this paper speculated about the future lives of Caroline and her daughter, and Professor McCormack had thought it was completed as far as she could do without further research. In a second remarkable coincidence, on Tuesday, 29 September, she met John Malcolm, a member of the Fort McMurray First Nation, who knew her history and confirmed for her something that she had heard to the effect that Caroline Arnott remarried in 1903 to Alexis Cree Senior, a man located farther up the Athabasca River (and Raphael Cree’s uncle).

She bore three other children with Alexis Cree, who died c.1911-12. Caroline then married a third time, in 1912, to Henry (Harry) Taylor Malcolm, with whom she had more children. Caroline’s daughter, Rosa Alberta Arnott (known as Rosa), like her mother before her, was placed in the convent as a two-year old toddler on 20 March 1902, to be raised by the Sisters. Professor McCormack could find no trace of her in the convent records searched, but John Malcolm informed her that she married Henry Militaire Hainault and had children of her own.

So both Caroline and Rosa have many descendants in at least two different Cree family lines. They are distant cousins to the descendants of James and Isabella back in Lewis, and one of my goals will be to find a way to build a bridge between the two families on the opposite sides of the Atlantic.

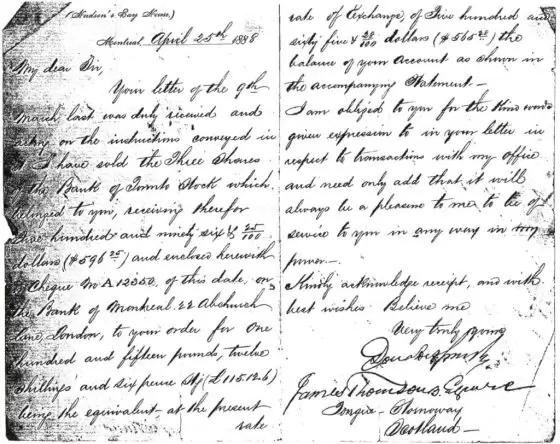

Letter from Hudson’s Bay Company

The letter opposite was sent by Hudson’s Bay Company on 25 April, 1888. This was three years after James and Isabella had returned to Lewis, so he seems to have instructed his former employers, to sell three shares in the Bank of Toronto and remit the funds to the UK. The amount transmitted was about £115 which is equivalent to about £18,300 at 2023 prices. The letter transcribes as follows:

Hudson’s Bay House, Montreal. April 25th 1888

My dear Sir,

Your letter of the 9th March last was received and acting on the instructions conveyed in it I have sold the three shares of the Bank of Toronto stock which belonged to you, receiving therefor five hundered and ninety six dollars & 25 cents. and enclosed herewith a cheque No A12350 of this date on the Bank of Montreal, 22 Abchurch Lane, London to your order for one hundered and fifteen pounds, twelve shillings and sixpence. (£115-12-6) being the equivalent at the present rate of exchange, of five hunderd and sixty five dollars and 28 cents, the balance of your account as shown in the accompanying statement.

I am obliged to you for the kind words given expression to in your letter in respect of transactions with my office and need only add that it will be a pleasure to me to be of service to you in any way in my power.

Kindly acknowledge receipt and with best wishes. Believe me, Very Truly yours, Donald Smith [Lord Strathcona]

James Thomson Esquire, Tongue Stornoway, Scotland

Lord Strathcona

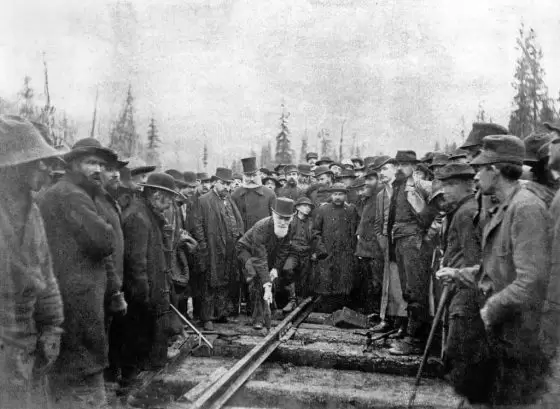

This paragraph and the previous paragraph share a common theme in that they mark the completion of a project. Both events were marked by the same man, Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona.

James Thomson had just completed some twelve years of working for the Hudson Bay Company. The final letter sent to him in Lewis enclosing the proceeds of the sale of his shares in the company was signed by Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona.

How fitting then that the final spike to complete the epic project to build a railway across Canada should be hammered home by Lord Strathcona himself. The railway the transported so many Lewis men across Canada.

James Thomson and Isabella MacIver

I believe that this photograph was taken in Lewis after James and Isabella returned to their croft at 15 Tong, Lewis, Scotland.

James and Isabella had ten children. The first three being born in Fort Chipewyan, and the remaining seven back in Lewis. Their first child was Marion Mary was born in Fort Chipewyan on 28 February 1882. Her story is told in the article The Family of Marion Thomson and is told by her daughter Jessie Mawhinney.

The other children were James Alexander 1883, Catherine 1885, Jessie 1888, Christina 1889, Alexander 1890, Mary 1893, Isabella 1894, Jane 1896 and Catherine 1899.

James died in Lewis in 1929 and Isabella died in 1947.

Update – December 2023

This page has been updated with some very helpful corrections and additional information and photographs provided by Brault Kelpin, who lived in Fort Chipewyan in his youth. I am very grateful to him for his contribution. He chanced upon this website while searching for information about James and Isabella. I am grateful to Brault for his help. He has written a fascinating blog about his early years in Fort Chipewyan and other fur trading settlements which I thoroughly recommend.

A detailed study of the Chipewyan Indian Nation can be found in Patricia McCormack’s Research Report ‘An Ethnohistory of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation’.