A Doctor at Anzio 1944

A Doctor at Anzio 1944

A Doctor at Anzio

This article was written by Dr Joe Turney who served with my father in 3 UK Field Ambulance (3 FA) throughout the Anzio Campaign. It is a fascinating personal account of life in the Anzio Beachhead.

Joe was a colleague and friend of my fathers, and their friendship endured after the war. They served together in 3 FA under the command of Lt Col P L E Wood, who my father always called ‘Plew’ as those were his initials. Joe told me that my father was always called ‘Tommy’ during the war. After my father died in 1991, Joe Turney sent me some personal recollections of my father and included the account below.

He first met my father on the troopship Tamaroa, sailing from Avonmouth to Algeria where 3 FA served in the North African desert, then Sicily and mainland Italy, until my father was promoted and moved to 14 Field Ambulance in the Appenines north of Florence.

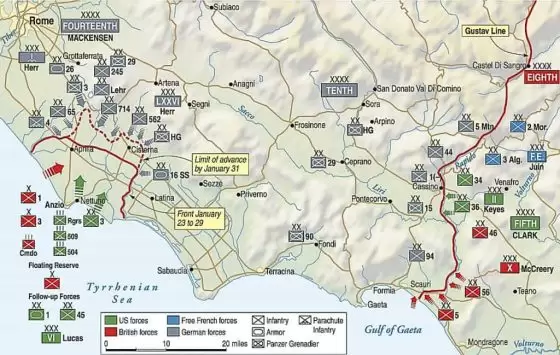

The Battle of Anzio commenced on January 22, 1944 and concluded with the fall of Rome on June 5. Part of the Italian Theatre of World War II (1939-1945), the campaign was the result of the Allies’ inability to penetrate the Gustav Line following their landings at Salerno. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill sought to restart the Allied advance and proposed landing troops behind the German positions. Approved despite some resistance, the landings moved forward in January 1944.

In the resulting fighting, the Allied landing force was soon contained due to its insufficient size and cautious decisions made by its commander, Major General John P. Lucas. The next several weeks saw the Germans mount a series of attacks which threatened to overwhelm the beachhead. Holding out, the troops at Anzio were reinforced and later played a key role in the Allied breakout at Cassino and the capture of Rome.

The rest of this article is written in Dr Turney’s own words.

Landing at Anzio

February 4th 1944 dawned bright and cold. I was the Regimental Medical Officer to the 2nd Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters having taken the place of Doctor John Burton who had been taken prisoner of war. Events later that day made me responsible also for the 1st Battalion of the Kings Shropshire Light Infantry (1 KSLI). The landing at Anzio had been successfully accomplished a fortnight before.

Campoleone

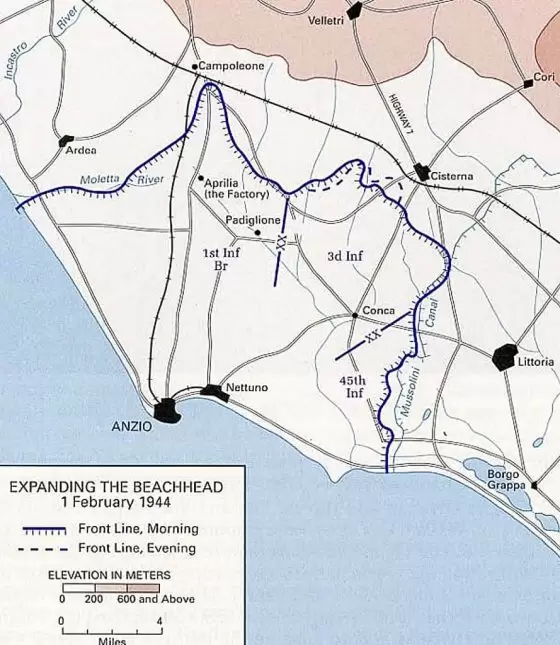

Some days before I had set up the Regimental Aid Post (RAP) in a shop in the village of Campoleone, 15 miles north of the port and the farthest the Allied penetration ever reached. At the time of our acquisition, the shop was in total disorder and seemed to have sold nothing but buttons and baby powder. In the relatively peaceful days before the counter attack we sorted out sets of buttons and some of mine eventually arrived home in a big tin.

Surrounded

The 3rd Brigade of the 1st British Infantry Division was holding a salient 2 miles long and 1000 yards wide on the road going north. The 1st Battalion of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the Kings Shropshire Light Infantry were forward with 2 Sherwood Foresters in support. On that day I was the most northerly placed Allied Medical Officer in Italy. In general, sanitation in rural Italy was primitive and as there was no toilet in the shop, we emerged soon after dawn to seek relief. To our amazement, two or three hundred yards to the south of us, straddling the road was a German tank. The salient had been cut and we were in a pocket.

Overview

The Anzio landing had been planned to overcome the months long hold-up of the Allied advance at Monte Cassino 60 miles to the south. The plan was well conceived; the intent was to land the 1st British Division, three American Divisions with support from Commandos and Rangers. The objective was to take the Alban Hills south of Rome, to control Highway 6 and 7 and so to cut the supply routes to the German front at Cassino.

Preparations

1 Div had landed at Taranto after the North Africa campaign in December 1943. It had proceeded northwards on the Adriatic coast with the proclaimed intent of joining the 8th Army on the East side of Italy. At Foggia, however, the main body turned west to cross the mountains in radio silence whilst representative vehicles continued north with radios chattering, hoping to deceive the Germans that the Division was still on it’s original axis of March. We settled in on the Positano/Amalfi peninsula at the southern end of the Bay of Naples to practise the art of assault landing.

Preparing the Equipment

The exhausts of the ambulances had to be waterproofed so that they would still function if they landed in up to 5 feet of water. After our idle time in North Africa following the fall of Tunis on June 4th 1943 we had to get fit. I marched my company of 3 FA up Vesuvius and we stood on the very rim of the active crater. We also toured Pompeii where our RAMC other ranks were fascinated by the overt sexuality of the carvings and realised that pornography was not an invention of the 20th Century.

The Initial Landing

The night of 21/22 January was selected for the combined operation. The division was embarked on a variety of types of ships. Our brigade commander discovered that his Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) had no doctor aboard, so I, with two stretcher bearers, was transferred by pinnace. The plan was for the 3 IB to be landed on a beach north of the port of Anzio. Our instructions were drummed into us, that we were to climb the beach, cross a coastal road and rendez-vous in the woods on the far side. I still carry a mental picture of what was required although I did not see the beach until 40 years later. Our little Armada accompanied by two cruisers and four destroyers, sailed from Castellamare in the afternoon of the 21st, first westwards, passed Capri but after dark on a northerly course. The other two brigades of the 1 Div including The Guards were designated to lead the landing at 2 am. They captured the town without significant resistance so that the 3rd Brigade enjoyed a dry landing on the quay. Our only excitement was when Paddy Johnstone, my batman, managed to get his stretcher impacted transversely on the disembarkation ramp completely halting the rapid evacuation of the LCI on that side.

In the words of Macauley “But those behind called ‘forward’ and those before cried ‘back'”. The fury of the Bridgadier was memorable. I rejoined my unit, at that time, 3 FA and we marched out of the town in extended order to minimise our target size. All was quiet and there was no sign of the civilian population. I never did discover what happened to the unfortunate inhabitants who seemed to have disappeared completely, although some weeks later an outbreak of gonorrhea in a Guard’s battalion was traced to a secret bordello some of them had organised.

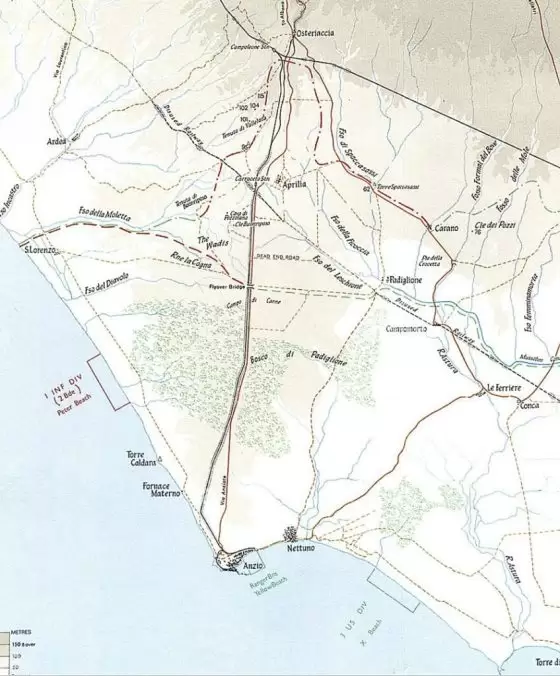

Four miles north of the port, we turned into the Padiglione Woods and dug ourselves in. This was my first experience of using my entrenching tool to dig a slit trench. I made it 2 feet wide and a foot deep, but unfortunately 1 inch too short for my height so that in the night it was impossible to stretch out.

The Advance

The next few days were peaceful enough; later we were told that we had surprised the Germans and had General Lucas our American Commander been bolder, we could have realised our objective and cut off the enemy’s army to the south. This same General was heard to say “by gosh, the Army has given me some strange jobs but never before to command in the field” Lt. Col. PLE Wood set up a blackboard outside HQ 3 FA showing our successful advance but this morale raiser disappeared when we faced reverses.

The MO to the 2nd Battalion Foresters was captured and on 28th January I was sent forward by jeep to take over in the salient. Most movement was by night as the Alban Hills provided a splendid look out point for the Germans over the Littoral plain. It was an experience to hear the field artillery first firing ahead and then to pass the guns clattering off with metallic voices and finally to find myself in front of the guns. On my way up, I saw my first dead soldier in Italy. A jeep had gone over a mine. Sitting upright in the back, stiffened in situ by rigor, was a US private with an equally dead cigar still clenched in his teeth.

Thus I arrived at the RAP in the button and talc shop. A moderate number of wounded came through every day but even at the front, the doctor dealt with more sick than wounded. I remember a KSLI Officer reporting with tonsillitis. and refusing my suggestion that he be sent back saying that he was due to lead a probing patrol to bring back a prisoner for interrogation. He failed to return to our lines. In a quiet phase, a tank crew nearby were out of their vehicle brewing tea, when they were mortared, I went across to find the driver had a shattered jaw.

He was lying on his back spluttering and cyanosed. We rolled him over and immediately his oxygenation was restored. Another day a tank received a direct hit. One of the survivors suffered bilateral fractured femora. With straps under his axillae my stretcher bearers hauled him through the turret and applied Thomas splints. These appliances were the standard first aid and for major leg fractures and the RAMC personnel were trained to a high level of efficiency in their use. They were taught literally to put them on when blindfolded.

Bren Gun Crew

Nearby to the RAP a Bren gun carrier was parked in a small quarry and its crew were sheltering in a cave on the back wall. The vehlcle was set on fire by enemy action and burning petrol shot back into the cave. The small arms ammunition on the carrier was going off like fireworks but without force or direction. In a quick rush we got behind the carrier and dragged out the burnt men.

So passed the week until 4th March when we discovered we were in the middle of the fight. An anti-tank gun had been dug in just outside my shop/RAP. I had protested that as I was flying the Red Cross. The situation contravened the Geneva Convention but the Gunners refused to budge. When they saw the tank straddling the road behind us they manhandled their gun through 180 and fired. The second round hit the tank broadside and a body was thrown into the air. The battle went on all day. At one point 150 British prisoners taken in our rear were being escorted northwards. As they passed a company of Sherwood Foresters some of the guarding Germans were shot.

Some prisoners were able to rejoin the British but others were made to continue the walk into captivity. They disappeared over a railway embankment but a KSLI major chased after them in a Bren gun carrier and a few minutes later the men returned, this time with the Germans as prisoners.

Treating the Wounded

The RAP continued to take wounded and by the afternoon we had exhausted our holding space. I decided to open an annexe in another shop across the road. I found that when crossing the street in one direction I came under small arms fire. The problem was solved by wearing a red cross armlet on both arms. At one stage a German Officer visited us and claimed we were his prisoners. I protested that I was the only doctor on site and that I had as many Germans as British wounded. He accepted the point and we did not see him again.

The need for a line of evacuation of casualties became imperative. An improvised Red Cross flag was made with paint and a towel and a Bren gun carrier was borrowed from the infantry. Across the carrier we set two loaded stretchers. It set off south down the road and disappeared from sight through the German positions.

I was very relieved to see it reappear half an hour later followed by an ambulance. The driver of the carrier, Sgt. Sowter was recommended for and later awarded the Military Medal. From then on I had an established evacuation line and was able to send back the more serious cases.

The Retreat

In the late afternoon I was told by telephone that the area would be evacuated at 6 pm and that the Brigade would retreat two miles to defend a better line. Five minutes after the withdrawal, the artillery would flatten the area to prevent close pursuit. All that could be taken was what we could carry. We opened the medical panier and shared out the medical comforts – two bottles of Brandy – a heinous crime in other circumstances. I left behind my bed roll containing a dressing gown. The Germans who found it, must have wondered at the way the British went to war.

A few minutes before 6 pm I was loading my last ambulance, I found I had five stretcher cases in four places. One was a German NCO and the other four were British. On the basis that one should whenever possible further the war effort I decided to leave the German behind. Just as we were about to move off a British soldier died. We quickly offloaded him and put the German aboard. I suppose he never knew how lucky he was.

At six o’clock we belted south along the road to our main position in single file, extended order. One shell landed on the road a few yards ahead of my detachment with a metallic clang and seconds later we walked through the shallow crater reaking of explosive. I reported back to the CO of 3 FA.

Advanced Dressing Station

An Advanced Dressing Station (ADS) commanded by Capt E W McQuade RAMC of 3 Field Ambulance had been set up in a small factory. This unit continued to function during the battle and came under machine gun fire. The unit carried on and gave 30 plasma transfusions that day. At length a mortar bomb crashed through the roof and another blew out the door. By the 7th February it was no longer possible to care for the wounded in such a place and the ADS personnel moved back. Later, it was discovered that medical stores and in particular, plasma had been left behind.

Lt Col Wood suggested that after dark I take a jeep and trailer and go to pick them up. I protested that I had never driven a jeep but my CO thought it would be a good opportunity for me to learn.

Artillery Support

We drove in an eerie quiet in no mans land to the building, stopped the engine, manhandled the vehicle round to point home, loaded the stores and prayed that the motor would start first time. It did, and we raced back to our positions. During the 6 days the Brigade held the salient our supporting 2 Field Regiment RA fired 23,000 rounds. The hot barrels of the 25 pounder guns had to be sponged out with cold water.

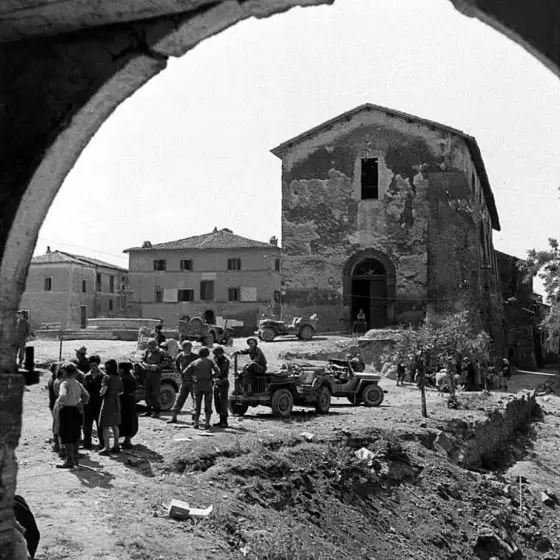

From 7 – 10 February the next line of defence for the British was around Carroceto and the so called Factory Area which in reality was a small monastery. Overwhelming attacks were put in and 1 KSLI was quickly put back into action to recapture a ridge to the east. The battalions came under heavy machine gun fire and all the officers in the two leading companies became casualties.

In the four months the beachhead lasted, 1 KSLI had 42 officer casualties, from a strength of 36, replacements also fell. The Factory area fell and the Allies retreated again to their last defensive line based on the Flyover Bridge and the Lateral road. The German plan believed to have originated from Hitler himself, was for an attack to be put in on our one north/south axial road splitting the Allied Forces and driving on to the ports of Anzio and Nettuno.

The German Counter Attack

On 16th February, preceded by an artillery bombardment,the attack came in. Two German divisions supported by 30 tanks managed to advance half a mile. A counter attack restored the position but the battle oscillated for 48 hours. Infantry battalions sent in their cooks and storemen and Field Ambulances deployed their RASC drivers. In the rear and so called ‘rest’ areas only two miles behind the front, we FA Doctors watched the digging of defensive back to back positions.

At the end of February the Guards Brigade was withdrawn. It had suffered heavy casualties and by custom, only accepted guardsmen as replacements. A final major assault was put in on the Americans on our right on 29th February but the line held. The beachhead had so shrunk that when a corps artillery shoot was ordered all the guns could be brought to bear on one section of the arc line front.

Thus the defended area was stabilised with Battalions rotating in and out of the line.

Malaria Precautions

As the weather became warmer the mosquitos started to breed. Supervised by the Field Hygiene Section, all units were made responsible for draining or oiling any stagnant water. Mepacrine was issued to the troops and as a rumour spread that the drug caused impotence, parades had to be organised to make sure the tablets were swallowed. The dosage at first was two tablets twice a week but because of nausea, diarrhea, headache and fever the regime was modified to one tablet given four evenings per week.

Digging a Fox Hole

Although the forward troops suffered privation in the rain and mud, in our rest area in the Padiglione Woods we gradually made ourselves safer and more comfortable. I dug myself a hole 4 feet deep which took my camp bed and an orange box as a bedside table bearing a candle. Over the top I p1aced two heavy doors from a local bank. These in turn were covered with sand bags surmounted by 160 pound tent.

Capt Rupert Gibson, our Dental Officer was a religious man and appropriately sheltered under the doors of a church. The vulnerable point in my dug out was the entry, and during the night air raids I lay in bed worrying about my feet being blown off when anti personnel bombs. called ‘red devils’ were shovelled down by the thousand by low flying aeroplanes.

Anzio Annie

In the day when medical duties were finished we spent our time visiting other units in the woods playing bridge or poker and watching aerial dog fights. Every so often we would hear Anzio Annie go overhead. This was reputed to be a 15 inch railway gun kept in a tunnel in the Alban Hills. It was aimed at the ports where the supply depots were densely packed. Space was indeed at a premium.

Some 50,000 men and equipment were packed into a fan shaped area with a radius of seven miles. We lived on compo rations. One box fed one man for fourteen days or fourteen men for one day. Everything was thought of, the boxes contained cigarettes, matches and lavatory paper. The tinned bacon was a particular favourite.

Minor Surgery

Minor surgery in the FA was performed on a stretcher on trestles. On one occasion I had to jump into a nearby slit trench in reaction to increased activity leaving the patient under light Evipan anaesthetic on the top. Not surprisingly, under such stressful conditions battle neurosis was seen. At one stage I remember in the Main Dressing Station (MDS) of the FA, I had six or eight stretchers laid out in a tented dug out for such patients. The treatment was simple, for 48 hours these casualties were kept heavily sedated. One man was literally scared stiff and could be moved like a plank. In the early days, we managed to get most of the men back to their battalions but officer casualties were a different matter.

Casualty Clearing Station

No. 2 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) was established on the axial road just behind the rest area of the combattants. It is now the site of the British Military Cemetery. It was within reach of the enemy field artillery and wounded men were again injured or killed. For the unfortunate patients lying on stretchers on the muddy floors of the CCS tents it must have been hell. Besides physical dangers, the troops were subjected to psycological warfare from loud speakers, radio and leaflets. The last were scattered widely by shell or aeroplane.

Some told how to feign illness“Make up your mind on one disease and stick to it, Never tell the doctor what is wrong with you, doctors hate that”. Advice was given on simulating tuberculosis to battle exhaustion. Slapping the knee was recommended to produce an effusion.

Fears of marital problems at home were induced “while you are fighting on the beachhead the Yanks are having a fine time with your wife” the last pamphlet was accompanied with an appropriate illustration. One of my Geordie stretcher bearers took one look and said “That doesn’t look a bit like my old woman!”

The Wadi Country

To the west of the Flyover Bridge in the static period to the break out in May the 3 IB in turn defended the Wadi country so named by the troops recently fighting in Tunisia where a wadi was a dry water course. The Italian wadis were anything but dry, being tributaries of the Moletta river. They formed complicated patterns bizarely named, for example, ‘The Boot’ and ‘The Lobster Claw’. This was trench warfare but with an ill defined front. Sometimes part of a wadi was held by us and the other end by the enemy. The banks were steep and it was possible to throw a grenade over the top and into the next wadi. In spite of the wet and cold conditions trench foot was not seen.

On the night of 21st May 1 KSLI was in the line and I was in my RAP behind the lateral road. The phone rang. It was the CO who explained that a man in a forward company had been shot in the neck and he wanted me to go to attend to him. I protested that there was nothing more I could do than was in the competence of my corporal who was with the Company.

The CO replied, that for the sake of the morale of the battalion he wanted the doctor to go forward. I set off with a guide along winding communication trenches to reach the Company HQ which was dug in on the reverse slope of a small quarry. By now the casualty had died. I was given a mug of tea and from this position we could hear the Germans talking and moving about.

Wounded in Action

Another casualty was brought in and I decided to accompany the stretcher party. The return journey was complicated by the fact that in accordance with normal military practice the supplies were being carried up at night. Our progress was constantly being held up by parties bearing water, food, fuel and ammunition.

Unwisely, I ordered the bearers to climb out of the trench so that we could make better time on the top. I took my turn on one front handle of the stretcher when there was an almighty bang. A mortar shell had landed amongst our group. I felt a blow on my back as though I had been hit by half a brick and my left arm dropped to my side. I thought “Oh no, my brachial plexus” but a quick wriggle of my fingers reassured me. The other front bearer was in a bad way bleeding heavily.

In the dark I could not find a wound but later I learned that he had died from a severence of an axillary artery. Since I have often pondered that the width of an army stretcher is 22.5 inches . I was helped back to my own RAP and transferred by jeep to the ADS and by ambulance through the MDS to the tented 14 CCS. At each of the earlier staging posts the RAMC personnel commiserated that one of their own should be a casualty and prescribed the traditional hot sweet tea and morphia so, as a result. when I arrived at the CCS I was very sick.

Battle Casualty

Later I was operated on by an American captain for a compound fractured scapula. My battle casualty card, which I still possess was altered from “serious wound left shoulder region” to “trivial injury”. I woke up next day in time to see my infantry friends streaming into the CCS injured in the attack that was to result in the break out from the beachhead and the capture of Rome.

I left Anzio on a stretcher and I was carried aboard the US Hospital Ship Seminole with a group of GIs. Our morale was instantly restored at the sight of the stunning US nurses. One of the GIs said to me “its no good making a pass at dem dames. Dem collar dogs, they just rule you right out”. I forebore to reply, it was not the custom of British Officers to wear badges of rank on their hospital pyjamas.

A Stranded Whale

As we boarded the ship each of us was handed a Purple Heart – a US award for being wounded. The cruise to Naples was blissful. While lying in bed in G2 General Hospital I heard on the radio of the opening of the Second Front in Normandy. At this time I had a high temperature. Blood was taken for a culture but the diagnosis was benign tertian malaria.

Two months later I rejoined 3 FA for another six months fighting in the Appennines south of the Po Valley.

The Anzio campaign was undoubtedly an expensive military failure but for those that served there, it was an unforgettable experience. Churchill said “I had hoped we were hurling a wild cat onto the shore, but all we got was a stranded whale”

Acknowledgments. The above account is mainly from memory although I possess certain maps and diaries relating to the period. For dates, military formations and sketch maps I am indebted to “Ubique” by A.M. Cheetham MC (Freshfield Books 1987).