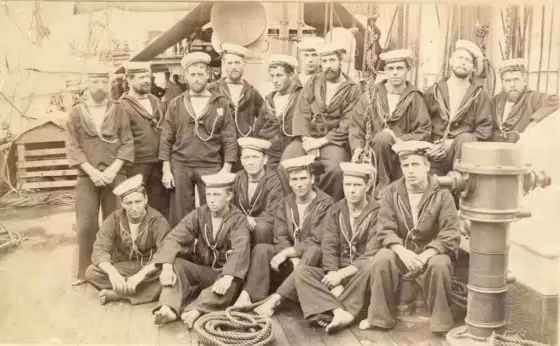

John Yeates Yeates and HMS Thunderer

John Yeates Yeates and HMS Thunderer

John Yeates Yeates

John Yeates Yeates was born John Yeates Richards at Park Head, Levens, Westmorland, England on 4 June 1826. His parents were George Yeates and Margaretta Brettargh. On 31 May 1837, John’s father changed his surname by Royal Licence from Richards to Yeates as a condition of inheriting the estate of his guardian Anthony Yeates, and so his son, John Yeates Richards became John Yeates Yeates.

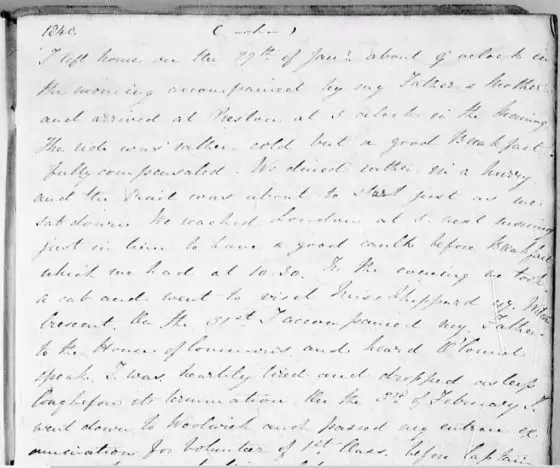

John Yeates Yeates’ father had served in the Royal Navy and was keen that his eldest son should follow him into the Navy, and so it was that at 9 o’clock on 29 January 1840, his son, at the young age of 13, boarded the Royal Mail Coach in Kendal with his parents bound for London and then Plymouth to join the Royal Navy.

John Yeates Yeates kept a Personal Diary for the duration of his service in The Royal Navy and this page has been based on selected edited extracts from his Journal. The story is told in John Yeates Yeates’ own words. A copy of the Personal Diary and the Ships Log that was copied by John as part of his service are available for download at the foot of the page.

Arriving in London

1840

I left home on the 29th of January 1840 about 9 o’clock in the morning accompanied by my father and mother. The ride was rather cold, but a good breakfast fully compensated. We dined rather in a hurry, and the Mail was about to start just as we sat down. We reached London at five o’clock next morning just in time to have a good caulk [naval slang for a sleep] before breakfast, which we had at 10.30. In the evening we took a cab and went to visit Miss Sheppard, 47 Wilton Crescent. On the 31st I accompanied my father to the House of Commons and heard O’Connell speak. I was heartily tired and dropped asleep long before its termination.

On the 3rd of February I went down to Woolwich and passed my entrance examination for Volunteer of the First Class, before Captain Phipps Hornby. Sir Charles Adams was kind enough to allow me to stay a month in town before my final departure at the same time giving me a hint that the process of fitting a ship out ought not to be overlooked as I might profit by it considerably in afterlife. I only stopped until the 22nd in London, when I embarked on board the Thames Steamer for Plymouth. It was then I felt the first pangs of parting with my dear parents. I feel bound to say though that I was very hard hearted at first for I was thoughtless and happy and cared little about the present. Circumstances prevented my father and mother from proceeding any further than London or it would have been grand to have seen the ships in that great naval rendezvous, Plymouth.

On the 24th in the evening at 10:00 o’clock we saw the lights at Plymouth but being too late to go onshore that night I contented myself with sleeping on board at Calwater. Next day having called on Captain Basden and left my trapes at his house I went down to Devonport to report myself to the commanding officer Captain Williams.

Devonport

March 7. The ship was warfed [sic] alongside the hulk to get her stores and ammunition on board. A hulk is an old unseaworthy ship jettied up expressly for the officers and mess of any ship fitting for sea. The “Vigo” was the name of the hulk, we were lashed alongside of. Her accommodation was not bad although it would not be to the taste of a young bear just left the nursery. I made myself very comfortable after duty was done, and in the evening, I could read, write, or do anything I liked. For nearly a fortnight afterwards we were employed stowing away salt provisions, water, tanks and receiving boatswains’, gunners’ and carpenters’ stores.

March 12. I accompanied Captain Basden and his daughter to a ball given by Mrs Fugle. It was a very gay and pleasant party and we kept it up until 3 o’clock next morning. I can assure you I slept very soundly after it all for I did not awake until 10.30 next morning when I incurred the displeasure of my commanding officer for being up so late.

March 17. Captain Williams was superseded by Captain Massey. A loss which we all felt for Williams was a man remarked for his kindness to his officers and at the same time a good disciplinarian which was the very reverse of his successor for I never saw a man with a worse temper. One day when I was standing on the combings of the chain hatchway seeing the shot called in, he told me to let him know when the first “fakes” of the hemp cable was down. Well, I did not know what a fake meant so you may imagine I was sometime before I found it out and got well rowed for being so long. However, I did not forget it in a hurry.

March 20 and 21. We were employed getting in guns, shot and carriages, Which completed the gunners’ stores , except the powder which is next sent on board when the ship is in the Sound, when it is sent off in a Lighter fitted up for the purposes.

April 8. The ship was towed down to Hamoaze on the other side of the harbour and painted inside and out so that by the 13th the ship was ready for both officers and men which was the day appointed for us to shift over from the hulk. Soon after we got on board the men were stationed as regular as possible in watches and divisions and the ships company had leave to go ashore in each of their watches so that we had always two on board and one on shore. I very often went on shore with the commander or master to the dockyard in the launch to bring off hawsers so that I generally had an opportunity of seeing the various ships repairing.

HMS Thunderer

April 15. Cambridge 80 guns anchored in the sound from Sheerness to see if she could pick up any men before proceeding to the Mediterranean.

April 16. Persian 10 guns sailed into the sound. The commanders name was Quinn, the same who was so attentive to me on my passage down to Plymouth. I have heard since that he died on the coast of Africa. On Good Friday, the skipper read the Articles of War at 2.30 pm. I got leave to go on shore to visit a mess mate. I also called at Captain Basden’s to see if he had returned from London.

April 18. Beat sails. Inconstant anchored in the Sound.

April 24. At 7 pm the Carron Steam Vessel took us in tow. As we passed the dockyard the houses and parapets, were covered with people cheering. But although our spirits were very high at that moment we were soon dumped by the report that Howard the quartermaster had been blown from the main chains by one of the saluting guns on the quarterdeck. He had been called out of the chains where he had been employed heaving the lead and it is supposed that while clearing the line the charge had blown him overboard.

The body was picked up in the water by pieces about the size of a brickbat. Just as we passed the Cambridge, the engine broke down which delayed us 3/4 of an hour. When we were once more moving, the steamer took us as far as the breakwater and when a light breeze sprung up, she left us. We took a short cruise round the Eddystone lighthouse and back again and anchored in the sound about five o’clock in the evening. Moored ship in 15 fathoms.

Plymouth, Devonport

April 27. Roding 92 guns anchored with the Broad Pennant of Sir Hyde Parker from the Mediterranean. At 7 pm the Persian sailed for the coast of Africa.

May 1. The wind blew very hard from the East which obliged us to strike the top gallant masts.

May 6. The captain gave all the youngsters leave to go on shore with his sons and play cricket with them at “Borsaw” the harbour masters residence. We spent the afternoon very pleasantly but were interrupted by heavy showers of rain. Mr Walker took us off in his gig in the evening after tea.

The scenery about the Sound is not very striking. The only place which draws the attention of visitors is Mount Edgecumbe the residence of the Earl of Edgecumbe. It is fitted out in his own style and the heights are covered with trees of every description. But adieu to Plymouth for the Mediterranean.

HMS Thunderer leaves Plymouth

May 23. at eight o’clock a.m. Her Britannic Majesty’s Ship Thunderer weighed from Plymouth Sound with a light northerly wind. The Harbour Master accompanied us to the Eddystone and then returned. I have turned in in very high spirits.

But I found myself transported next morning when I turned out with inconceivable velocity to the lee side the steerage. When I went on deck the scene of the preceding day had changed considerably. Instead of smooth water and all sail set, we were under close reefed topsails and courses with a heavy head sea.

May 30 & 31. We had beautiful weather and the air felt warm and delightful. Saw several porpoises. On June 2nd we anchored at Lisbon directly opposite the town. I could not go on shore because my leave was stopped but I had a very good view of the town. The houses seem of all colours and the streets are of the filthiest description possible. We found the Donegal 78 guns, Revenge 78 guns and Espoir 10 guns with some men of war of foreign natives.

On the 4th we again weighed with a south west wind in company with the Revenge. In tacking we slightly touched the ground on the opposite side under the cliffs but soon got off again. We reached the mouth of the Tagus but were obliged to anchor on account of the floodtide making. We weighed again at slack tide.

The Egyptian Ottoman War 1839 – 1843

In the early nineteenth century the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul ruled a vast empire that stretched from Libya in the west to the Arabian Gulf in the east, and from what is now Romania and Serbia in the north to the Sudan in the south. A weak central government, all too often bedevilled by corruption and by difficulties in communication over such a vast area, made it easy for local governors to set themselves up as semi-independent rulers.

The most notable of these ambitious local governors was Muhammad Ali (1769 – 1849), an Albanian general in the Ottoman Army who was appointed governor of Egypt in 1805. His first step in consolidating his power was to eliminate the Mamluks, the warrior caste which had ruled Egypt, under the Sultan, for over 600 years. He did so in 1811 by inviting the Mamluk leaders to a celebration at the Cairo Citadel. Once gathered there, they were surrounded by Muhammad Ali’s troops and slaughtered. He was now de-facto ruler of Egypt and the Sudan by the 1820s was arguably as powerful as the Sultan himself.

Muhammad Ali asked the Sultan for Syria, a term which then included modern Lebanon and Israel in addition to the country now known as Syria. The Sultan refused and in the early 1830s Muhammad Ali, successfully seized Syria, and much of Arabia, in a campaign that was notable for Ottoman ineptitude.

A mixture of medieval despot and enthusiast for modernisation, Muhammad Ali now concentrated on building Egypt into a powerful and independent European-style state. No opposition was allowed, and the process was often brutal. He set out to streamline the economy, train a professional bureaucracy, and build a modern military machine. He not only encouraged agriculture – the global demand for cotton was insatiable – and he built an industrial base, primarily focused on weapons production. By the end of the 1830s, Egypt’s war industries had constructed nine 100-gun warships and were turning out 1,600 muskets a month.

Sidon

In 1839, the Ottoman Empire, now ruled by the young Sultan Abdulmecid, attempted to retake Syria. Ottoman ground forces were once again routed.

In June 1840, the entire Ottoman navy defected to Muhammed Ali and the French Government, with aspirations to regain the control of the area which Napoleon had won briefly, then lost, decided to offer full support to Muhammad Ali. This would involve a major strategic reorientation in the Middle East and indeed held the seeds of a general European conflict (WW1 seven decades too soon!). Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia decided that preservation of the Ottoman Empire was paramount and decided to intervene jointly to prevent total collapse.

By the “Convention of London”, signed in July 1840, these powers offered Muhammad Ali and his heirs permanent control over Egypt, the Sudan and the “Eyalet of Acre” (an area roughly corresponding to modern Israel, Palestine and Southern Lebanon) as nominal territories of the Ottoman Empire. Muhammad Ali hesitated, believing that he could rely on French support. This was a fatal miscalculation.

British and Austrian naval forces moved into action in September 1840. Faced with the possibility that confrontation with Britain could mean war, France, pragmatically but ingloriously, changed sides the following month, aligning itself with the other European nations against Muhammad Ali. By this time the Royal Navy and the Austrian Navy had already been in action. Alexandria, to where the defecting Ottoman fleet had withdrawn, was blockaded and forces were concentrated on Sidon and Beirut on the Lebanese coast.

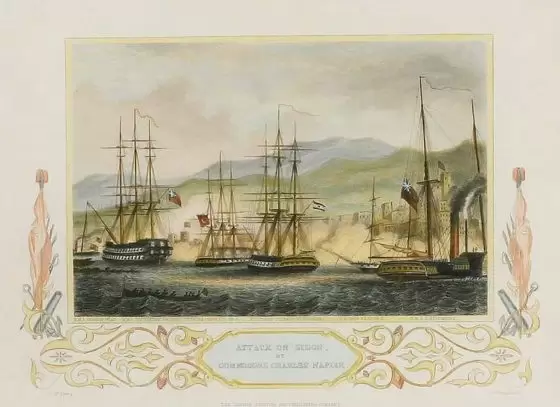

At Sidon, the withdrawal of the Egyptian garrison was demanded by the British commander, Commodore Charles Napier (1786-1860). A refusal brought bombardment by Napier’s squadron on September 27th. This force was led by the HMS Thunderer, a two-deck 84-gun ship of the line, launched in 1831 but not significantly different to ships of the Napoleonic era.

Sidon

The bombardment seems to have driven the Egyptian defenders from their positions and, in the best Royal Navy tradition, a naval brigade landed under Napier’s personal command, suppressed any remaining opposition and captured many prisoners. Beirut was subjected to similar treatment but did not yield until October 9th, after Napier had again landed and had conducted a vigorous and successful land campaign.

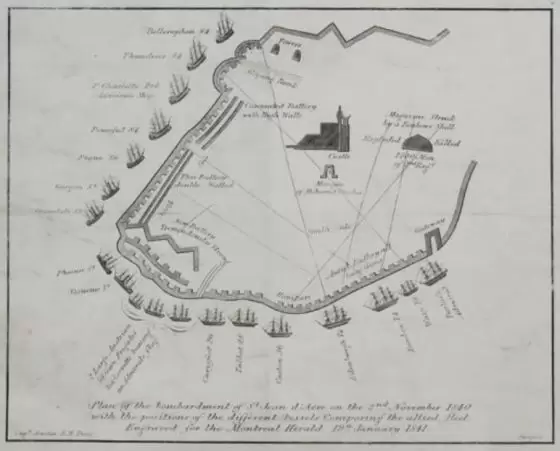

Acre (just north of Haifa) was the remaining Egyptian stronghold on the Eastern Mediterranean coast. British and Austrian forces, attacked again, led by HMS Thunderer. Following a bombardment on November 3rd, 1840 a small landing party of Austrian, British and Ottoman troops, led personally by the Austrian fleet commander, Archduke Friedrich, took the citadel after the Egyptian garrison had fled.

Muhammad Ali now accepted the inevitable and assented to the terms of the Convention of London on November 27th. He renounced his claims over Crete and Western Arabia and agreed to hand back the Ottoman fleet and to downsize his remaining naval forces and standing army. In return he and his descendants would enjoy hereditary rule over Egypt and Sudan.

HMS Thunderer was to serve on towards the dawn of a new age of naval technology and 1863 was fitted with iron plates for trials of new armour-piercing guns. She survived as a storage hulk until 1901, initially renamed Comet, and subsequently Nettle, one of the last links with the age of fighting sail.

Sidon

September 23. I had charge of the first and second cutters to tow the Zebra down to Saint Georges Bay to attack the bridges. All the marines of the squadron were embarked on board the steamers, and landed at Djounie Bay a very advantageous place selected upon by the Commodore for erecting a tent to contain troops and where they might have time to build a fort free from the molestation of the enemy, who were likely to pass that way.

The Edinburgh was employed most part of the week in firing at the enemy as they passed along the high road. The bombardment commenced with all its fury that day. We were dispatched to St. George’s Bay to prevent the bridge being used in their retreat from the town and in consequence preventing the English from landing at Djounie. The effect was very grand at night seeing the ships firing, and the Austrians through their Congreves remarkably well.

Royal Marines

Before they had been on shore ten minutes I was roused from the harmless occupation of smoking a cigar by the report of musketry close to the boat on the beach we pulled in and succeeded in bringing off the party.

It was a hugely dangerous attempt to land there on a bright moonlight night within 1000 yards of a camp said to be filled with 10,000 men which was the case, but it was done to find the position of the bridge which if an enemy was seen to cross we had only to burn a blue light on the ship would have opened her broadside upon them.

While we were employed getting the party into the boat she was touching with the bow and the fellows came down to the beach and fired deliberately into her. How anyone escaped is a miracle for some struck the boat while the rest whizzed harmlessly over our heads. An Austrian boat was with us at the time which cut and run on the first musket being fired and left us to bring off her officers.

At Djounie our force suffered some loss by the attack of a fort strongly built and covered with loopholes from which such a destructive fire issued that are brave fellows file fast on every side and obliged then to retreat. The camp at Djounie was built chiefly of sandbags carried to the top of the hill by the seamen and marines of the squadron. I was onshore as Aide de Camp to the Captain every other day from 4 pm to 4 am next day, and then relieved by another midshipman from the Ganges.

During our stay here hundreds of Druses came down from the mountains to join us and were all supplied with muskets. Sir C Smith the General of the forces was on shore with us. He seemed a very fine man but was very fond of having too much of his own way. The young Prince of Austria was also one of our brother campaigners. He was only 19 and yet had the command of a fine 50 gun frigate under the command of Mr Bandeira.

The Battle of Acre

November 3. At 4 am the boats were hoisted out, hammocks stowed and then we went to breakfast. It would have done anyone’s heart good to have seen the execution done, cocoa and bread swing to the expectation of a battle.

After breakfast the bulkheads were cleared away, guns loaded all ready for action the moment the signal was made. We did not wait long for at 1030 the Admiral weighed as did the rest of the squadron in succession. The breeze was very light from the westward so that we had time to dine.

The squadron rose and stood in, the batteries firing a few shots as the ships came round opposite tack. The Western line was led by Sir C Harper in the Powerful 84. The southern line was held by the gallant Castor which acted her part to the admiration everyone under a heavy fire from the batteries. 2:15 pm squadron anchored, and the action became general at 2.30.

At three the enemy’s powder magazine blew up with a stunning noise, the air all round was covered burning shells, mud, stones et cetera. Broadside after broadside was fired until 5 pm in darkness coming on; we hauled out of gunshot to repair damages.

The Surrender of Acre

Next morning, I went on shore. The sight was actually sickening. The number of dead and dying wretches laying in the street and on the ramparts was immeasurable. The walls are of immense thickness and mounted all round with very heavy guns, not a soul was to be seen in the town where ever we went except Austrian and Turkish soldiers ransacking the dead soldiers.

But the disgusting scene may be better conceived than described. The storehouses on the western walls were completely destroyed and rendered walling rather than rather dangerous on account of the shells being hurled about in all directions. But this is not all we went to the eastern part of town to the place where the magazine had blown up.

We were obliged to turn our heads with disgust at every step. Men, women and children lay indiscriminately around with the mutilated bodies of sheep, oxen, pigs and asses, which had huddled into the square for safety. Before the enemy sent their flag of truce they had made good their retreat from the town only to fall into the less merciful hands of the Druzes who fell upon the unfortunate creatures and killed a great part of them.

They were brought into the town. The Admiral, soon after the action, held a council of war to storm the city on the land side. The beach was made for us without our knowledge for the explosion had destroyed the rocks and scattered stones all about the plain.

The Aftermath of Acre

We had upwards of 900 Egyptians on board us as I mentioned in a former part of this narrative, who had expressed themselves willing to serve us. Every ship in the fleet had a proportionate quantity of them in case of storming the town. I shall not soon forget the yell of joy they gave on the explosion taking place.

The number of killed to the enemy was between two and three thousand. The prisoners when sent on board the different ships accounted in all 7000 men. The damage done to the squadron very slight considering the whole affair. We had our preventer main brace and part of the captain’s cabin window shot away. The most severe was the Commodore and Revenge they had both their top gallant masts badly wounded, the former shot away and main top mast badly injured and three men killed between.

On the southern side all the ships escaped with slight loss except the Castor, she had 23 men killed and wounded amongst the former was Lieutenant L. Mevure, who was killed first shot a splinter striking him in the belly. Her injuries about the foremast and bowsprit were very severe so much so that she sailed for Malta soon after the action besides having several shot below the water.

We sailed on the fifth in company with the Bellerophon I forgot to relate a very singular and some may think very improbable anecdote. A man in the barge on the opposite side to the engaged saw a shot come through the midship lower deck port and fall close alongside. This was corroborated by the officers of the foremost lower aft quarters as perfectly true. What a providential thing; at the least it might have mown down 6 or 7 men.

Original Documents

This article has been prepared from the Yeates Family Documents and Diaries, the original copies of these documents have now been donated to the Kendal Record Office and have been made available to the public for viewing or download.